WYNONIE HARRIS – “MISTER BLUES” – THE REAL FATHER OF ROCK AND ROLL **

By Cindy Allingham, Oct. 7, 2022

In the 21st century, when we go looking for roots of music genres, we typically dig up old video footage and consult accredited music experts.

It is not surprising that most listeners under 80-years-old think of Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Elvis Presley and Little Richard, active from 1956 on, as the earliest icons of Rock and Roll. A recent comment by a friend on Facebook singled out Berry as being the “father of rock and roll”. I challenged this comment by mentioning Wynonie Harris; my friend had never heard of him and took the opportunity to listen to the 1949 King recording called “Good Rockin’ Tonight”. He changed his mind. (This was a cover of the tune by Roy Brown, made in the mid-40s.)

After World War II, African American men and women gathered for parties and dancing in urban clubs, as many other Americans did.

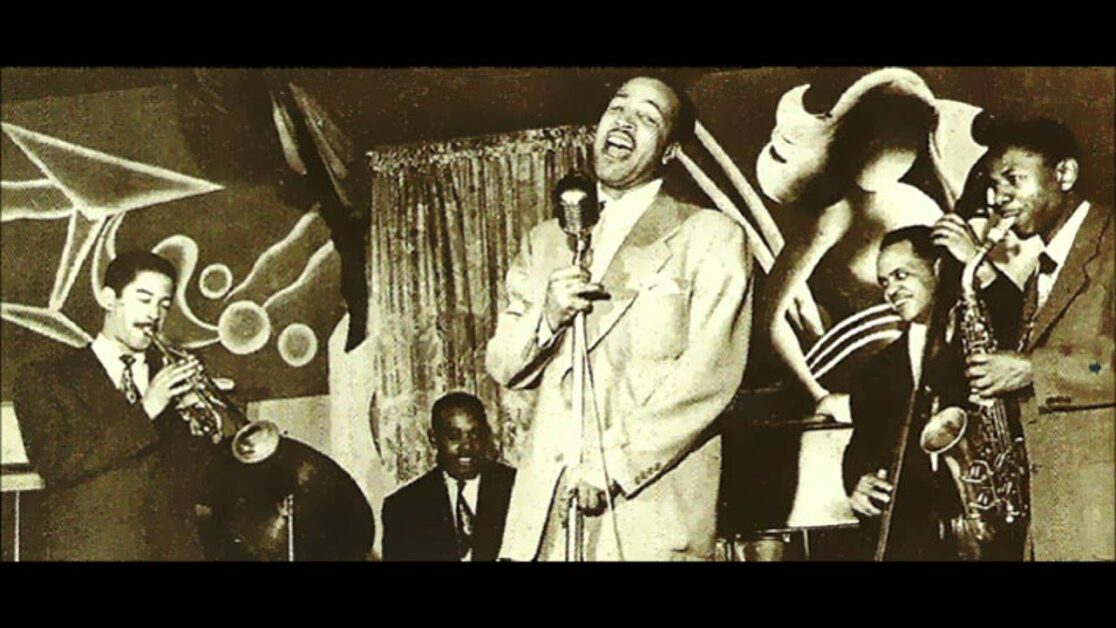

A music genre termed “Jump Blues” became popular in ballrooms; musicians who formerly played with large jazz bands formed smaller, more ‘portable’ groups and charged less to play. Louis Prima, Jimmy Rushing, Louis Jordan, Buddy and Ella Johnson, Roy Brown, Charles Brown, Big Joe Turner and T-Bone Walker were examples. And Wynonie Harris. He started out as a band singer for Jack McVea, Illinois Jacquet, Johnny Otis, Oscar Pettiford, and other bands in the 1940s, but went out on his own in 1946.

Jump Blues was all about fun on the bandstand.

In the days when “rock and roll” was a euphemism for sex, and dancing was another expression of attraction between the sexes, the lyrics had to be outrageous and the rhythms infectious. Nobody, but nobody, did it like Wynonie Harris. Sadly there is no existing video footage of him performing. His popularity was wild for a few years only, then dropped off. The stories about his almost lewd hip movements onstage convince me that Elvis watched him and copied him. His hard drinking and his womanizing were legendary.

The production of “race” records is a whole separate history, and well worth researching.

The beginning of the ‘crossover’ of race records to white audiences came about in the late 1940s when record companies would unload boxes of them in white record stores. My father was one of the mobs of white kids in urban areas who avidly searched through those boxes for popular jazz 78’s. “Good Rockin Tonight” by Harris was one of those he found, along with Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Horace Silver and Duke Ellington.

Dad told me that he first heard Harris, however, on a broadcast from New York showcasing Lionel Hampton’s orchestra. He sang “Good Rockin Tonight” and my dad had to find the record in a Toronto shop.

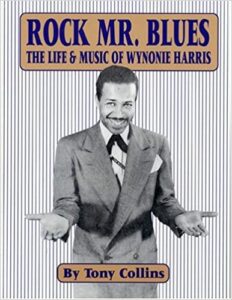

Tony Collins published a biography of Harris in 1995, “Rock Mr. Blues: The Life and Music of Wynonie Harris”.

Although this is now out of print, used paperback copies can still be found online (avail on Amazon). It seems like the definitive source for details about Harris’ life, as it is widely quoted. Collins describes how Harris, born in Omaha in 1913, became one of the premiere black performers in elite black clubs.

He was a handsome, light-skinned man with blue-green eyes and an irresistible smile. Between 1949 and 1952 he commanded a thousand dollars a week for his performances. Harris also dabbled in hypnosis for entertainment.

Collins claims that, despite his popularity with black audiences and interest from young white record-buyers, after 1952 Harris became a victim of the reality of segregation in music.

White promoters were afraid of his rampant sexuality and felt that they could find other white performers to do the job. Harris became demanding over money and insisted (unsuccessfully) on trying to maintain control of his performances, records and recording work.

His heavy drinking began to take its toll on his ability to perform; he insisted he needed alcohol to take the edge off the hoarseness in his voice, which increased throughout the 1960s. Eventually he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and passed away in 1969. The blues singer Jimmy Witherspoon, a friend of Harris’, sang at his funeral.

Collins’ biography does an excellent job of detailing his recordings and his work career, although it does little to describe specific dates.

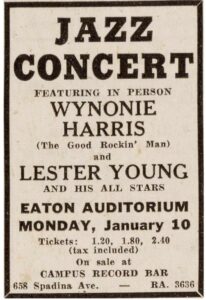

His appearance on January 10, 1949, at the Eaton Auditorium in Toronto, is considered to be the first rock and roll show in Toronto, according to Daniel Tate and Rob Bowman in The Flyer Vault, (Toronto: Dundurn Publishing, 2019).

Also on the same bill was Lester Young, and the 1200-seat Auditorium billed the concert as a jazz performance, but according to Tate and Bowman, no Toronto newspapers reviewed the show.

Collins’ book fills in a lot of information about Harris’ life, and explains much about why his popularity was short-lived.

Only listening to his music will explain the audience attraction. Every song includes a driving backbeat, raucous horns, and Wynonie’s raw-yet-silky voice. The lyrics of each song sound familiar to modern audiences, and phrases are found in rock and roll, soul music, and 1970s-80s blues.

But Wynonie’s lyrics were meant to be sexy and fun and ‘way beyond the pale for the late 40s and early 50s. He was not the first musician in the blues tradition to use double-entendres (phrases that have more than one meaning). Rock and roll referred to the sex act, but the lyrics for every song had their own stories and references. Don’t just read the titles; listen to the fabulous voice! Fortunately, he recorded quite a few of his bandstand favorites and I can listen all day long.

Wynonie Harris Recommended Playlist

1949 – Good Rockin Tonight

1949 – Grandma Plays the Numbers

1949 – All She Wants to Do is Rock

1950 – Sittin on it All The Time

1950 – Oh Babe!

1950 – I Like My Baby’s Puddin

1951 – Bloodshot Eyes

1952 – Lovin Machine

**feature image WYNONIE HARRIS by Esoterica Art Agency