The West Side Soul of Chicago Blues

Originally Posted on –Blues For A Big Town

As told numerous times, the emergence of Urban Blues was a by-product of the Great Migration of African Americans from the southern U.S. to points north. Undoubtedly affected, (for different reasons), by the Great Depression (1929-1933) and the War, millions of Blacks left the South for the urban centres of Atlanta, Memphis, St. Louis, cities in the U.S. West Coast, and predominantly Detroit and Chicago. An estimated 1.6 million Blacks made the trek north.

The migrants were typically farm workers / share croppers at home – including those moonlighting as musicians – and those that chose to make music a full time occupation.

They were drawn to said northern locales by the need and attraction of potential employment – especially the manufacturing jobs – that cities like Chicago had to offer. (It was not uncommon for musicians to work as a labourer by day and Bluesman at night in their adopted home).

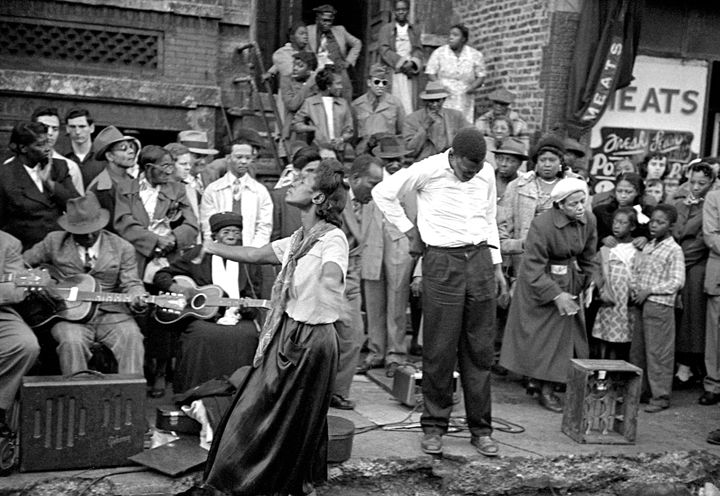

The new arrivals brought their customs and rituals as well as their music. That music, so integral to their daily lives, was usually comprised primarily of “Hillbilly” fare – complete with fiddles, hoedowns, and square dances – and, of course, Country Blues. In most instances the prevalent form of Blues was the Delta Blues variety that originated in the Mississippi Delta.

The Mississippi Delta Blues can be generally characterized as direct and emotionally intense, and stands as arguably the most influential of the various Blues styles.

In its most basic setting Delta Blues musicians played solo accompanying themselves on rhythmic, percussive acoustic guitar, often employing a slide or bottleneck. And, the player might be joined, at times, by a backing musician playing harp (primarily) and / or fiddle, and / or second guitar.

With the move to the city both the songs that were performed and the instrumental accompaniment were adapted to the new urban environment. While some themes remained, lyrics moved from country life to that of their new city surroundings. And Blues ensembles evolved, adding electric guitar, amplified harp, piano, and later a rhythm section of bass and drums.

(It should be noted that slide guitar maintained its place – as a pillar of Blues music in general). The full blown band not only ratcheted up the intensity but also enabled the performers to be heard above the din of the rowdy and joyful crowd that frequented the many Windy City clubs.

In the 20’s and 30’s the first wave of Delta Bluesmen such as Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy, and Sonny Boy Williamson 1 (John Lee Williamson) were the forerunners who gained popularity and became well established in the Chicago Blues musical community.

After 1945, they gave way to a new generation of Bluesmen including Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, Sonny Boy Williamson 2 (Aleck “Rice” Miller), and Little Walter.

Racial discrimination as it was forced Waters et al to take up residence and make their living on the South Side of Chicago.

That being the case, and since they were the highest profile artists, when Chicago Blues and the associated legendary clubs are mentioned most everyone immediately assumes that any such talk is referring to music played on the South Side.

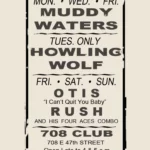

No doubt there were numerous, (and famous), clubs on the South Side: Pepper’s Lounge, Theresa’s Lounge, Big Duke’s Blue Flame, 708 Club, Smitty’s Corner, Cadillac Baby’s, The Trocadero, and The Castle Rock among others that featured live music up to seven nights a week.

But just as Blacks were relegated to the South Side due to segregation so too were Blacks confined to the West Side of Chicago for the same reason.

(The West Side had been mainly a Jewish neighbourhood whose population moved to the North side or to the suburbs).

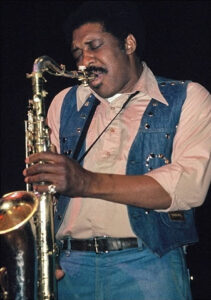

And, as in the case of the South Side, West Side musicians mostly lived and performed in their own area of town. As sax player Eddie Shaw, who started his career on the South Side with Waters and Wolf before taking up residency on the West Side, explained: “Most of the time we didn’t usually play on the other’s turf”. (While this may have been somewhat the norm, both South Side and West Side musicians would go wherever the dollar led them).

Just like their counterparts in the South Side, the West Side had its own share of clubs that enjoyed notoriety: 1815 Club, Mel’s Hideaway Lounge, (later named Alex Club), Sylvio’s, Club Zanzibar, The Squeeze Club, Curley’s Twist City, Walton’s Corner, The Tay May, Big Bill Hill’s Place, and The Copacabana.

West Side Blues emerged in the late 50’s as West Side players acted as change agents setting themselves apart from the “old guard”.

They used the established style as a base and expanded on it by adding their own distinctive take on the still recognizable Delta Blues. Similar stories in song continued to be told, but while the established voices of the Blues kept it somewhat insular, the new players were open to new influences and thereby incorporated Gospel, R&B, and tinges of Rock & Roll.

In keeping with the new wave approach, West Side players altered instrumentation as well. They generally eschewed the harp in favour of one or two sax players. And when the economics didn’t allow the addition of horns West Siders compensated by emulating the sax sound with their guitar phrasings.

They also presented themselves differently on stage as well. While club audiences were accustomed to the musicians sitting down, West Side artists preferred to stand as they performed thereby providing an additional dimension of stage presence as they energetically pushed their music forward. In so doing, they modernized and breathed new life into Chicago Blues with an electrifying new style.

While true to the original form, West Side players shared commonalities with the new white interpreters of the idiom on both sides of the Atlantic.

Chicago’s West Side guitar players tended to display an aggressive style; playing it raw, loud and hard, heavy on the vibrato and reverb. And, although West Siders played fewer notes with comparatively a lot more sustain, they were just as inclined to stretch out and jam like their white counterparts bringing screaming guitar to the forefront. West Side guitar player Jimmy Dawkins described it this way:

“The West Side is bare; it’s down to the blood-line. We played hard-core, bone-crushing Blues; the sound was raw, strictly from the throat and stomach”

Jimmy Dawkins

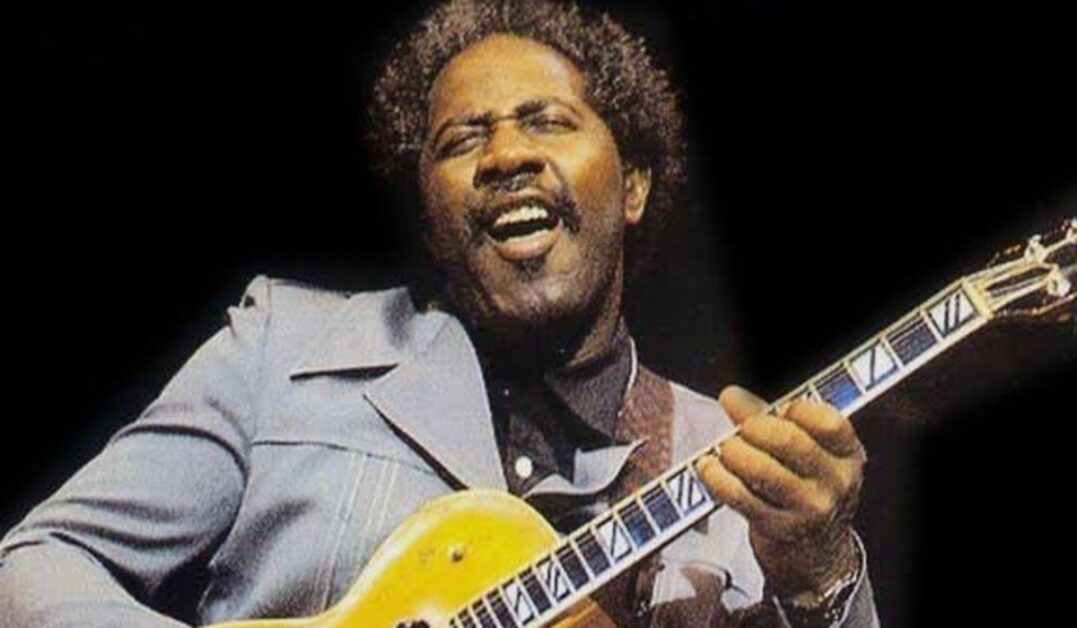

Although it may seem contradictory, they played in that fashion but did so with an eye to the clean guitar lines of B.B. King and drew on the emotionally charged vocals they heard by the likes of Ray Charles. And like B.B., the best West Side guitar players truly sang as well as they played.

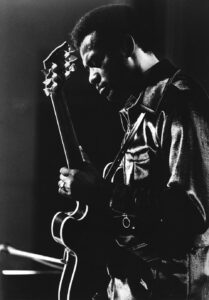

While open to conjecture as to who was the initiator, the unquestioned champions of this new breed were Magic Sam and Otis Rush.

As the leaders, they influenced a long line of West Side creators including Buddy Guy, Freddie King, Jimmy Dawkins, Luther Allison, Mighty Joe Young, and Byther Smith among others. (Freddie King, originally a Texas guitar player, is mentioned because he played an integral role in shaping the West Side guitar sound when he took up residency in Chicago in the years 1950 through 1963).

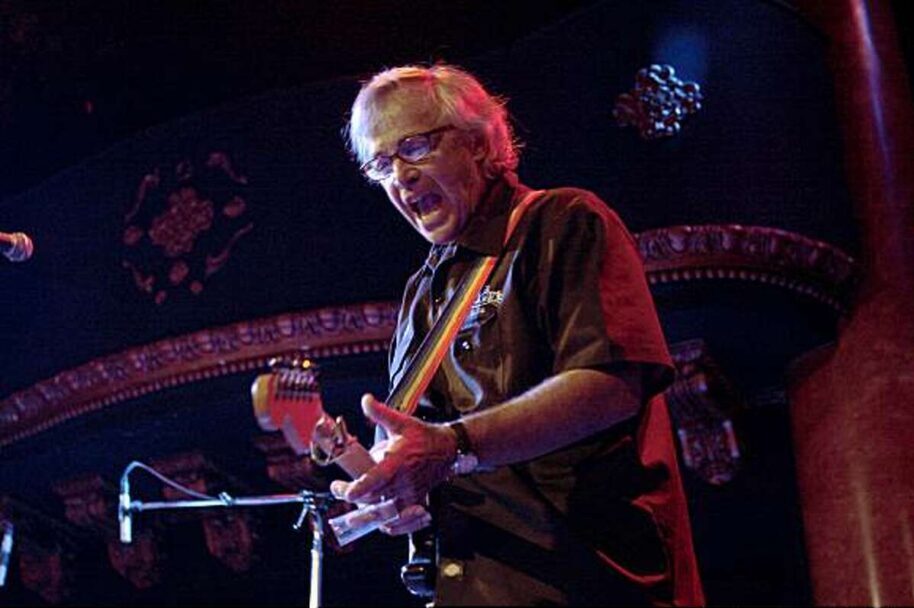

It’s indisputable that Buddy Guy – who Eric Clapton once called “The best guitar player in the world” – with 9 Gammy Awards and 34 Blues Music Awards, (the most any artist has ever received), over more than a 60 year career, is the most celebrated of the above mentioned artists.

In fact, he has rightfully earned his place as a true Blues icon alongside the likes B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Little Walter. Also, it goes without saying that the flamboyant Guy is part of the triumvirate of West Side Blues standing shoulder to shoulder with Magic Sam and Otis Rush.

But given all of that, it can’t be discounted that his initial entry into the hearts and minds of Blues fans was provided by Magic Sam and Otis Rush, the acknowledged pioneers of the West Side Blues sound.

In keeping with that mindset, the respective stories of Magic Sam and Otis Rush – major forces in the genesis of Chicago’s West Side Blues – deserve to be told in greater detail.

(It should be noted that songwriter and producer Willie Dixon and Cobra Records, synonymous with the birth of West Side Blues, played a major role and warrant attention as well).

Otis Rush, who predates Magic Sam’s arrival on the scene by a couple of years, was known for his impassioned, full throated vocals and highly inventive guitar playing. He was a major influence on Michael Bloomfield, Eric Clapton, and Elvin Bishop among other “name” guitar players. (Not to mention that John Mayall’s singing style leaned heavily on Rush’s vocal tendencies).

Rush, from Philadelphia Mississippi, was born one of seven children on April 29, 1934. While Rush did sing in the church and started playing guitar at eight years of age – learning from watching his older brothers play – there was no music tradition in the family as such.

The family was preoccupied with working in the fields, and, for his part, Rush didn’t take playing the guitar seriously at that point. Members of the family did listen to Country Music radio, and Rush learned to pick out some notes to Eddy Arnold, Bill Monroe, and Hank Williams offerings.

In the course of learning to play guitar, being left handed, and his brothers being right handed, it never occurred to Otis to re-string the guitar to play it conventionally

– that is with the thickest, lowest-pitched string at the top of neck and the thinnest, highest-pitched string at the bottom of the neck. In effect, Rush played the guitar “upside – down”. As he said:

“When I put it on it was strung right-handed and I just began to learn that way by ear… I just began to learn notes and some chords…”.

Otis Rush

When Rush was 15, he visited his sister in Chicago. In what turned out to be a major turning point in young Otis’ life, his sister took him to a club to see Muddy Waters.

Thrilled with the experience Rush decided right then and there to move to Chicago permanently. He worked various labour jobs by day, and spent the nights hawking the clubs for his new found heroes and, now taking the guitar seriously, practicing steadily.

At 19 years of age, Rush made his first public appearance when he came to the attention of the owner of a club – The Alibi.

When the act that was booked to play cancelled at the last minute, Rush was asked to fill in. Otis didn’t have a band but elected to play solo and was well received. Accordingly, doors started opening for Rush who played with various bands at a number of local clubs on both the South and West Side of town.

As he gained the invaluable experience of playing live, Rush continued practicing; immersing himself in B.B. King and T-Bone Walker records as well as taking lessons from ex Bo Diddley and Howlin’ Wolf sideman Jody Williams.

Rush kept honing his craft over the next few years, and started to establish his own unique, innovative guitar style complete with jagged notes, sustained licks and lines.

In short, he did things on guitar that other – lesser – players wouldn’t even think of doing. Rush coupled those twists and turns with forceful, frenetic, almost out-of-control vocals.

He built enough of a following that in 1956 he had a South Side residency at the 708 Club with a band including Louis Myers on second guitar and Fred Below on drums. It was at the 708 Club that Eli Toscano, the owner of the fledgling Cobra Records, was introduced to Rush.

That introduction was made by legendary bass player, songwriter, and then Cobra Records talent scout and producer Willie Dixon. (Dixon had left the employ of Chess Records, frustrated that he couldn’t convince Leonard Chess to sign acts that he had personally scouted. Rush was one of Dixon’s suggestions).

It would prove to be a fortuitous moment because Rush would go on to be the most recorded artist on the Cobra roster, and the label would be a key component in the establishment of the West Side sound as Toscano would not only sign and record Rush but also Magic Sam and Buddy Guy as well.

From 1956 through 1958 Otis Rush would go on to record 16 sides, (singles were the order of the day), for Cobra pushing Toscano’s second hand equipment to the limit. Most of the releases were written, arranged and produced by Dixon. Dixon also brought another attribute to the table, that of being able to attract top flight musicians to the sessions. Included in that list were: guitarists Wayne Bennett, Ike Turner, Jody Williams, Louis Myers, and Matt “Guitar” Murphy; piano players Little Brother Montgomery and Lafayette Leake; Little Walter on harp; and Fred below on drums.

Cobra struck gold on the first release.

Backed by a band including Bennett, Leake, and Dixon on Dixon’s “I Can’t Quit You Baby” Rush’s anguished vocal and multi note attack dominate the track. And the public took immediate notice as the cut reached number 6 on the R&B Top Ten. (The uninitiated may associate the song with Led Zeppelin’s tepid, histrionically heavy version on their first album).

It can truly be said that virtually all the tracks merit attention. (I say that with the question “what was Dixon thinking?” on “Violent Love”).

That being said, 2 entries rise above the rest. The last session in 1958, utilizing Ike Turner’s band on Turner’s echo laden arrangements, produced the classic “no job, no love” lament “Double Trouble” and the timeless Rhumba inflected “All Your Love (I Miss Loving)”. Both stand up years later, and were popularized by The Butterfield Blues Band (“Double Trouble”) and John Mayall / Eric Clapton (“All Your Love”) respectively.

Unfortunately, Rush’s success at Cobra was short lived. Toscano, an incessant gambler, lost all of his money and was forced to close the doors in 1959.

That ended a short but highly successful run while playing a vital role in the birth of the West Side sound. (It may be of interest that Toscano was said to have underworld ties and died under mysterious circumstances in 1966).

But Rush had made his mark, and his success at Cobra made it possible for him to hire an outstanding band – possibly the best band he ever had. Along with 2 saxes, Rush’s band boasted Jody Williams or Earl Hooker manning the second guitar chair. This hot band played both South Side and West Side venues on a regular basis including Pepper’s Lounge, a mainstay of Rush’s.

Rush was gigging regularly but without a label or releases of any sort when he was approached by Sam Charters at Vanguard Records in 1965 to be part of a Chicago Blues compilation: Chicago / The Blues / Today!, (street date 1966).

In what would be a highly influential release of 3 separate albums showcasing James Cotton, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, and Otis Spann, Big Walter Horton, and Charlie Musselwhite among others.

The Otis Rush Blues Band, (featuring Luther Tucker on rhythm guitar), contributed 5 selections on the second album including a credible remake of “I Can’t Quit You Baby”. Undoubtedly, the performance earned Rush new fans as the collection has been cited by many people – this writer included – as their initial in-depth door opener to Blues and Chicago Blues in particular.

The following year, back in Chess Records’ good graces, Willie Dixon brought Rush to Chess for another try.

But two years with the label resulted in the release of one worthy song – the fine “So Many Roads, So Many Trains”. So Rush was on the lookout for another label. He signed a five year deal with Duke Records that would produce one substantial release, “Homework”, that The J, Geils Band would make their own on their debut album. (It’s doubtful that the general Blues audience had ever heard the original).

Feeling that his time had passed him by, what followed for Rush were a number of albums, mostly live efforts, with a lot of hits and misses in what would often be a commonplace lifeless, offhanded approach put forth by Rush. However, there are 2 albums that are consistently good and serve notice that Rush was still a force to be reckoned with: Mourning In The Morning and Right Place, Wrong Time.

The 1969 release “Mourning” on the Atlantic subsidiary Cotillion was Rush’s first full length album.

It was cut at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals with The Swampers including Duane Allman backing him. Produced by musicians / fans Michael Bloomfield and Nick Gravenites, the album features a number of highlights including the titles: “Working Man” (a Gravenites & Bloomfield co-write), “Reap What You Sow” (a Butterfield, Bloomfield, & Gravenites co-write), and a cover of B.B. King’s “Gambler’s Blues”.

Right Place, Wrong Time, which was released in 1976, on Hightone Records was actually recorded for Capitol in 1971 but put on the shelf because the powers that be at Capitol felt the product left a lot to be desired. Capitol, with a history of miscues, was wrong still again. “Right Place” finds Rush at the height of his powers on ten songs.

Once again highlights abound with Ike Turner’s “Tore Up”, Albert King’s “Natural Ball”, a speedy cover of Little Milton’s “Lonely Man”, Rush’s own title cut, and a moving version of Tony Joe White’s classic “Rainy Night In Georgia” among them.

Otis Rush would release his last album in 1998 – Any Place I’m Goin’ on the House Of Blues label – before his health started to fail him.

An originator and leader in the West Side Blues movement, Otis Rush passed away on September 29, 2018 from complications resulting from a stroke.

“No Blues guitarist better represented the adventurous modern sound of Chicago’s West Side more proudly than Magic Sam”

Bill Dahl, Music Historian & Writer

“I’m a Bluesman, but not the dated Blues – the modern type of Blues. I am the modern type of Bluesman. But I can play the regular stuff and I’m also a variety guy. I can play the Soul stuff too”

Magic Sam

The mercurial Magic Sam distinguished himself in a relatively short but highly influential 12 year career.

(Guitar stalwarts including Michael Bloomfield, Eric Clapton, and Duane Allman cite the effect that Sam had on their playing). More visceral that his West Side compatriots, Otis Rush and Buddy Guy, Sam inserted a good measure of his rural background influences into his sound. In fact, due to his local community leaning more towards Country than Blues per se, when he hit Chicago in 1950.

Sam played in a more of a Country / Hillbilly style than a straight ahead Blues vein. (His Country leanings may have served as an inspiration to pluck the guitar strings in that Sam didn’t play with a pick). It was only after listening intently to Muddy Waters and Little Walter – in addition to friend, (Blues / Soulman) Syl Johnson, teaching him Blues and Boogie – that Sam began to “urbanize” his sound.

Samuel Gene Maghett (February 14, 1937 – December 1, 1969), was born in Grenada Mississippi.

Although his immediate family wasn’t musically inclined, Sam was taken with music, and namely guitar at an early age. It was stuff of folklore that, not owning a guitar, a young Sam made and played Diddly Bows, (baling wire nailed to the side of a barn), and later cigar box guitars to fill that void. But, it must be said that Sam proved to be a quick study once he got a guitar, in that when he left for Chicago at 13 years of age he was a relatively skilful player.

It was Sam’s preoccupation with the guitar and his aversion for farm work that prompted his move to Chicago.

The story goes that Sam was subjected to several beatings at the hands of his father due of his refusal to help in the fields. In turn, his Aunt Lilly and her husband, harmonica player “Shakey Jake” Harris, agreed to take Sam off his family’s hands and let Sam move in with them in Chicago.

With future sometime sideman Harris’ guidance and encouragement, Sam soon started sitting in with various musicians around town and joined the Morning View Special a West Side Gospel group, thereby furthering his vocal skills while leaving an indelible mark on those same vocals. At 17 years of age, Sam decided to drop out of school and pursue music on a full time basis.

By the following year he was gigging regularly usually fronting a guitar / bass/ drums 3 piece. With Sam’s driving rhythms and tremolo heavy lines on full display the trio produced a full wide sound. It was also at this time that he played in Homesick James’ band amping up James’ traditional Blues by injecting searing guitar solos.

In 1957, the 20 year old Sam, presented material to Chess Records, and, like Otis Rush before him, Sam was turned down.

And also like Rush, Sam, in turn, was signed by the West Side Blues label Cobra Records. At the time of his signing his stage name was “Good Rockin’ Sam”. Eli Toscano, the owner of Cobra, suggested that a name change might be in order. After a number of names were bandied about Sam’s sometime bass player, Mac Thompson, came up with “Magic Sam”– a play on Sam’s name, (Maghett, Sam).

And with the release of the debut single and instant hit “All Your Love” on Cobra, so started the short but highly productive recording career of Magic Sam.

Magic Sam would record 8 singles on Cobra from 1957 through 1959.

Sam was hugely popular in Chicago and his records sold well. Unfortunately, as his career was building, Sam was drafted into the army. Despondent with his livelihood and dream derailed, Sam deserted. Receiving a dishonourable discharge, Sam was sentenced to 6 months in jail.

Sam struggled after his release from prison. With the demise of Cobra in 1959, Sam turned to Mel London’s Chief Label. Although he recorded 8 sides for the label, nothing of any significance resulted. (London noted that Sam had lost his confidence and the fire that was a signature of Sam’s Cobra recordings).

Sam continued to try to find some inspiration and cut 4 sides with Germany’s L+R label and 2 more with Otis Spann on the Crash label to no avail.

In response Sam took a 2 year hiatus from recording but continued gigging regularly with his own band as well as playing with Otis Rush.

Amidst all the failed attempts at recording his live flame never burned brighter and it was proven time and again that Sam had a loyal fan base. One of those fans was promoter and Delmark Records owner Bob Koester who recalled seeing a young Sam for the first time:

“I first heard Magic Sam on one of the great Cobra 45’s, later at The Alex Club at Roosevelt and Loomis on Chicago’s West side in 1962. Muddy called him up to the bandstand; Sam tripped on an electric cord and sparks flew! His playing and singing was even more electrifying”.

Koester, who played an integral role in promoting the growth of Chicago Blues in general, would be part of West Side music history by signing Magic Sam and releasing two landmark Magic Sam albums: West Side Soul and Black Magic.

West Side Soul effectively established the West Side sound, and set a new standard for Chicago Blues. The album was cut live in the studio, (with no overdubs or extra effects), in 2 days in 1967. Joining Sam was fellow West Sider Mighty Joe Young on rhythm guitar on 12 tracks including a remake of Sam’s first Cobra hit “All Your Love”. Also included on the album that Living Blues Magazine would cite as one its’ top ten “desert island” Blues albums are an outstanding cover of J.B. Lenoir’s “Mama, Mama – Talk To Your Daughter”, and the definitive urban take of Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago”.

Black Magic was cut in 1968 and released in 1969 just days short of Sam’s untimely death.

It contains a new version of the Cobra recording of “Easy Baby” and along with “I Have The Same Old Blues” remains a Magic Sam signature tune. Mighty Joe Young is once again on rhythm guitar, and the set includes “name” musicians Eddie Shaw on sax, and Lafayette Leake on piano.

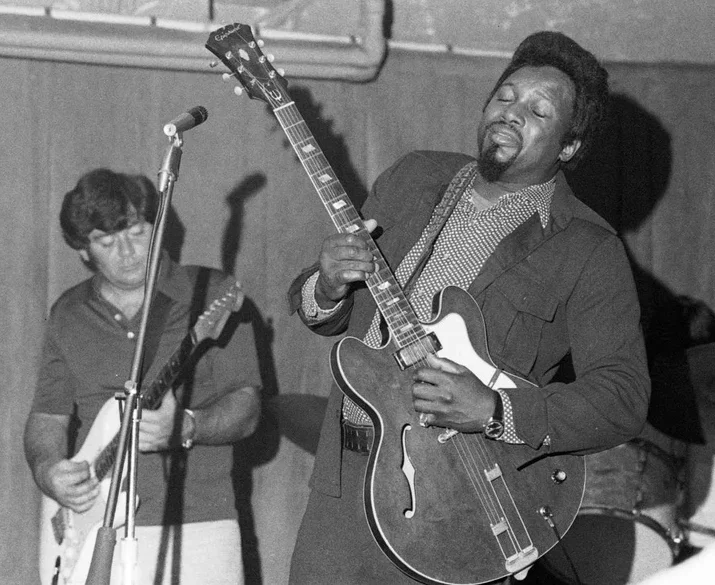

Sam toured both Nationally and Internationally in support of West Side Soul and cemented his strong West Coast fan base, especially in San Francisco where he played The Fillmore West and Avalon Ballroom, and had planned to return on a regular basis. A key date was the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival. Added to the bill at the suggestion of Bob Koester, the star studded line-up of both Country and City Blues artists included: Muddy Waters, B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Rush, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Son House, Junior Wells, and Luther Allison.

Sam’s appearance didn’t look too promising when he showed up late accompanied only with his bass player,

Buffalo Bob Barlow. Explaining that he didn’t have a regular drummer, Sam quickly enlisted the services of Sam Lay who luckily was playing that day. No further apologies were required as Sam stole the show. The publication Blues Unlimited, reported on the event (captured on the 1969 release Magic Sam Live): “The music alone moved the people who weren’t expecting it from someone they’d never heard of. And they screamed for him the rest of the evening”.

Other high profile gigs were soon to follow and Sam’s future appeared to be a bright one in that he was set to sign with Memphis’ Stax Records. (Koester, not wanting to stand in his way, agreed to release him). But Sam’s recurring health issues were making matters difficult.

After fainting in Louisville Kentucky Sam returned home to Chicago for a short stay only to embark on a tour to California and Europe. Returning to Chicago, Sam complained of heartburn and said that he was going to lay down for a rest. He collapsed before he got to the bedroom. Magic Sam Maghett was pronounced dead as a result of a heart attack at 32 years of age.

While providing some history and context on Chicago Blues, my hope is that this article will shine a well-deserved light on Magic Sam and Otis Rush, the kings of West Side Blues.

** I’d like to acknowledge the help and guidance of author and musicologist Bill Dahl in the writing of this article. Bill set me straight on Chicago’s South Side and West Side clubs as well as hipping me to a book that proved to be a great resource – Chicago Blues by Mike Rowe.

A Suggested West Side Blues Playlist

- Rico Ferrara, August 2021