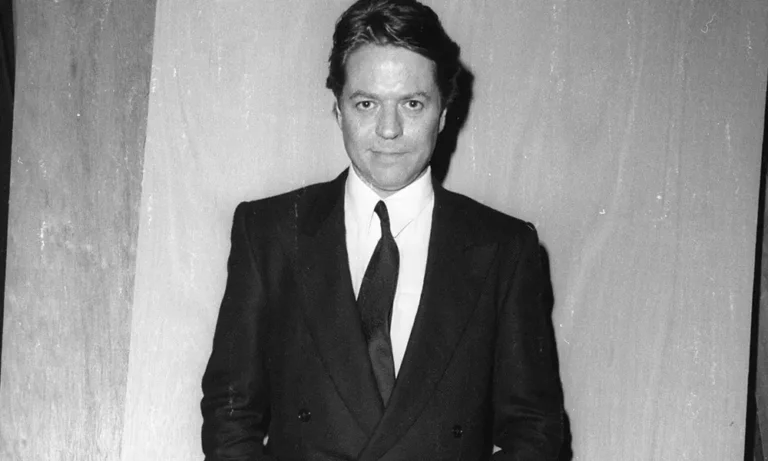

Robert Palmer – More Than Meets The Eye

“In interviews I hardly ever get asked about music. I do, however, get asked about the ‘Addicted to Love’ video and my suits on a daily basis”

Robert Palmer

Say the name Robert Palmer and it immediately sparks a mental picture and associated comments re: Palmer’s MTV defining video of his biggest hit, “Addicted To Love”.

The video shows a relaxed Palmer nonchalantly singing the song while fronting a “band” of beautiful models in tight black dresses. While certainly a captivating image, and, what would be, for most artists, a crucial moment; for Palmer it proved to be a temporary stop, at a point in time, in his musical journey.

To fully understand, one has to accept the fact that Robert Palmer was the antithesis of a Rock star.

That statement takes into account his interesting background, his reluctance to get caught up in the trappings of the Rock lifestyle, and, perhaps most importantly, his desire / willingness to grow and experiment with his musical choices in the face of a record buying public that doesn’t readily accept change.

Robert Allen Palmer, (1949 – 2003), was born in Batley, West Yorkshire England, and moved with his family when he was 3 months old to various locales as dictated by his father’s work as a British intelligence officer.

That being the case, Palmer spent most his childhood years in Malta, Gibraltar, and Cyprus which provided him with more of a global view of matters. During this time Palmer claimed that he had never seen a movie or watched TV. Instead he spent his days “at the beach”, admitted to being a lonely child with few friends, and one whose time was primarily in the company of adults.

Palmer also recalled his love of music being cultivated via his parents’ record collection, and nights spent falling asleep to the radio listening to the likes of Lena Horne, Nat King Cole, Peggy Lee, and Billie Holiday on American Forces Network. (Some years later, Robert would make his initial music purchase, the 1965 release, The Great Otis Redding Sings Soul Ballads. The album would serve as a foreshadowing of things to come while heavily influencing his singing style).

The family returned to England in 1961, when Robert was 12 years old, settling in the resort town of Scarborough, on England’s North Sea coast.

At that time young Robert was interested in many forms of exotic music that no doubt was influenced by his family’s various residences. Although music was a passion that led to Palmer singing with his first band The Mandrakes; he wasn’t convinced that music was, in fact, his true calling. That being the case, Palmer studied graphic design while pondering his future.

It wasn’t long, however, after his move to London, that Palmer joined a 12 piece Jazz / Rock Fusion Band, Dada, that included singer Elke Brooks.

Dada morphed into Vinegar Joe – a Rock / Blues outfit that found Robert playing rhythm guitar and sharing vocals with Brooks. Although the band built a reputation as an electrifying live act on the UK concert circuit, they couldn’t get any traction on their 3 albums, and disbanded in 1974, tired of the grind of the road.

That same year, Island Records, a British–Jamaican label founded by Chris Blackwell signed Palmer to a solo deal sensing that the eclectic Palmer would fit well with their varied roster that included Bob Marley & The Wailers and Toots & The Maytals. Over the course of his nine releases on the label, Palmer would prove to be a soulful singer with an amazing range and great taste. And, coupled with his dapper looks, a readymade persona.

The label would reap immediate benefits with Palmer releasing his outstanding debut, the New Orleans R&B soaked Sneakin’ Sally Through The Alley.

Backed primarily by The Meters and Little Feat’s Lowell George, Palmer proved himself to be a worthy torch bearer of cool and committed Blue-Eyed Soul at its finest. The album kicks off with a three song medley stringing together George’s “Sailing Shoes”, Palmer’s own “Hey Julia” and Allen Toussaint’s title song that sets the tone for one of the year’s best releases. Using a similar “Sally” template as a base, his next release, 1975’s Pressure Drop, is cited by many, (this writer included), as Robert Palmer’s high water mark.

With Little Feat, (minus Lowell George), and the Muscle Shoals Horns, Palmer navigates through nine interrelated entries.

Bookended by the gorgeous opener “Give Me An Inch” and the Sam Cooke inspired closer “Which Of Us Is The Fool”, the set proves that Palmer is rivalled only by Boz Scaggs in composed sophistication. But don’t be fooled; Palmer can get hot and steamy in a heartbeat. For proof just listen to Palmer’s “Fine Time” or the title cut, (a Toots & The Maytals’ cover that demonstrates Palmer’s affinity for Reggae).

The “Drop” follow-up, Some People Can Do What They Like, while not hitting the heights of either “Sally” or “Drop”, is a worthy descendant of “Drop” and forms the last part of a trilogy served up as a collection of Robert Palmer’s finest recordings.

Maintaining the stylish sheen of “Drop” it counters by favouring a more of a stripped down approach on what can be rightly positioned as Palmer’s Funk album.

He’s in fine voice throughout on a number of memorable musical moments. The album starts out with a mournful lost love appeal – “One Last Look”, a stylistic partner to “Give Me An Inch” written by Little Feat’s Billy Payne and his ex-wife Fran Tate – before getting to the business at hand. The business of Funk.

Of note are Little Feat’s “Spanish Moon” that, riding on a heavy bottom end, Palmer slows down to a strut; the slippery syncopation of Charles Wright & The 103rd Street Band’s “What Can You Bring Me”; and the frenetic heavily James Brown influenced title cut. “Some People” also displays, for the first time, Robert’s affection for rolling island rhythms by injecting the same into a cover off Don Covay’s “Have Mercy” and bringing Calypso into full view on Harry Belafonte’s “Man Smart (Woman Smarter)”.

To provide clarity, the success of Sneakin’ Sally Through The Alley / Pressure Drop / Some People Can Do What They Like was more of an artistic achievement than a revenue generating endeavour.

Despite heavy FM play, these works didn’t raise Palmer much above cult status resulting in paydays that were likely acceptable at best. Unfortunately, subsequent releases failed to capitalize on the artistic promise of the so-called “trilogy”, primarily due to the Palmer’s wandering musical tastes. That is, every one of Palmer’s releases had something to recommend them but the various albums couldn’t be pigeonholed for a music buying public that demands such categorization. He still revisited the accepted R&B style that found favour going forward but there wasn’t enough to entice significant purchases resulting in a number of commercial failures.

All was not lost at this juncture in that, to his credit, Palmer was consistently a great live performer; sure to sell out wherever he played.

He always surrounded himself with top flight talent that was well rehearsed. Much like one of his idols, Otis Redding, Palmer was known to be a task master who was a stickler for tempo. And, of course, adding to the cause was that Palmer was always in good voice, (the quality of which he attributed to chain smoking Dunhills and his fondness for single malt scotch).

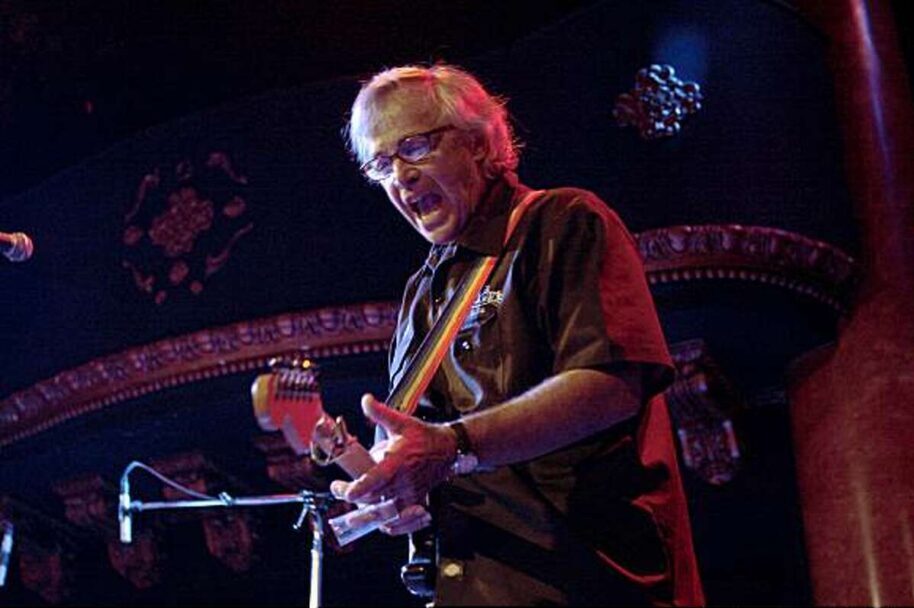

The next significant album – once again not notable for marketable success but rather for a sudden change in direction – was the 1980 album Looking For Clues.

The release has withstood the test of time, and, in retrospect, has its admirers lauding the release for the forward thinking venture into Technopop. But, at the time, such an unforeseen left turn was puzzling and surely looked like commercial suicide. In fact, in an interview with Toronto’s CITY TV’s “New Music”, Palmer was asked quite bluntly how he could turn his back on a successful formula to abruptly enter the New Wave / Techno arena. (Palmer had even shed his tailored suits for a chopped white sweatshirt bearing a UPC, track pants, and high top shoes in the accompanying videos and supporting tours).

Palmer’s response was just as blunt. He remarked that he didn’t want to be typecast as “an R&B saviour”, and that he had varied musical interests which, as an evolving artist, he should be allowed the freedom to explore. He also said that he saw the move as creative growth and hoped that his fans accepted it as such, and would be willing to follow him. And, in saying that, the album does contain some outstanding tracks such as the churning title cut, “Johnny And Mary” that brings Palmer’s considerable songwriting talents to the fore, and a striking remake of the Beatles’ “Not A Second Time”.

More releases followed that once again failed to move the needle before Robert decided to be part of a side project with his friends John and Andy Taylor of Duran Duran.

The band, The Power Station, maintained some Duran Duran like slickness, and added a crunching hard rock guitar sound rounded out with a pronounced bottom end. Palmer’s commanding vocals rode on top, and while matching the collective’s drive, added a dollop of soulfulness. (It should be taken into account that a hard edged Rock sound wasn’t foreign turf for Palmer. He had shown Rock tendencies in the past as evidenced by recordings like “You’re Gonna Get What’s Coming” from 1978’s Double Fun and Palmer’s first hit single, Moon Martin’s “Bad Case Of Loving You” from 1979’s Secrets).

The resultant release was a hit, producing 3 Top Ten singles including “Some Like It Hot” and a cover of T-Rex’s “Get It On (Bang A Gong)”. (Incidentally, of “Get It On,” Palmer said that when he read the lyric sheet he thought the song was ridiculous, and that the only way that he could pull it off was to “camp it up”). Palmer balked at touring with the band because he didn’t want to go on the road with a line-up of just 8 songs. That, and coupled with the fact that he was currently working on his next album.

That next album was Riptide which went to the top of the charts for several weeks on the strength of the (in)famous “Addicted To Love”.

While overshadowed by “Addicted To Love”, in all fairness, Palmer should be given some credit for other very good songs that are included in the set like “Hyperactive”, a refined version of Earl King’s “Trick Bag”, “I Didn’t Mean To Turn You On”, and “Discipline Of Love”.

In the context of a lot of the music of the day, “Addicted To Love”, (that earned Palmer his first Grammy), doesn’t need to be defended. But it has its’ detractors based almost solely on a video of what’s viewed as a mindless sexist power chord vamp. What’s lost is that its’ appeal lies in its’ very ZZ Top like simplicity. Further, I’m sure the song would be viewed quite differently had it been released as it was initially intended. The song was originally recorded as a duet with Chaka Khan, (who Palmer credited with the vocal arrangement). However, at the last minute, Khan’s management had Khan’s vocal track erased because they felt that the song would detract from the three singles she had out at the same time. (And, of course, any accompanying video including Chaka is left to speculation).

Palmer had finally broken through to the mainstream so it was an obvious decision to capitalize on his new found fame by repeating the formula with his next single “Simply Irresistible”.

Complete with the complementary video of Palmer at the mic surrounded by gyrating models, “Simply Irresistible” would hit and garner Palmer a second Grammy. But the album it was drawn from, Heavy Nova, unfortunately didn’t follow suit. The juxtapositioning of heavy Rock with romantic standards, (e.g. Palmer covers Peggy Lee’s “It Could Happen To You”), led to buyer confusion and resistance.

Given the state of the industry, and the ephemeral nature of record buyers, Robert Palmer had an opportunity to grab the brass ring but had lost consumer trust by failing to stay with the winning formula established with “Addicted To Love” and “Simply Irresistible”. This skepticism would make it even harder, given Palmer’s continued “moving target” approach, to make any headway with future releases.

True to form those upcoming albums would contain diverse offerings of Adult Contemporary, R&B, World Beat, and Blues, (sometimes all on the same record).

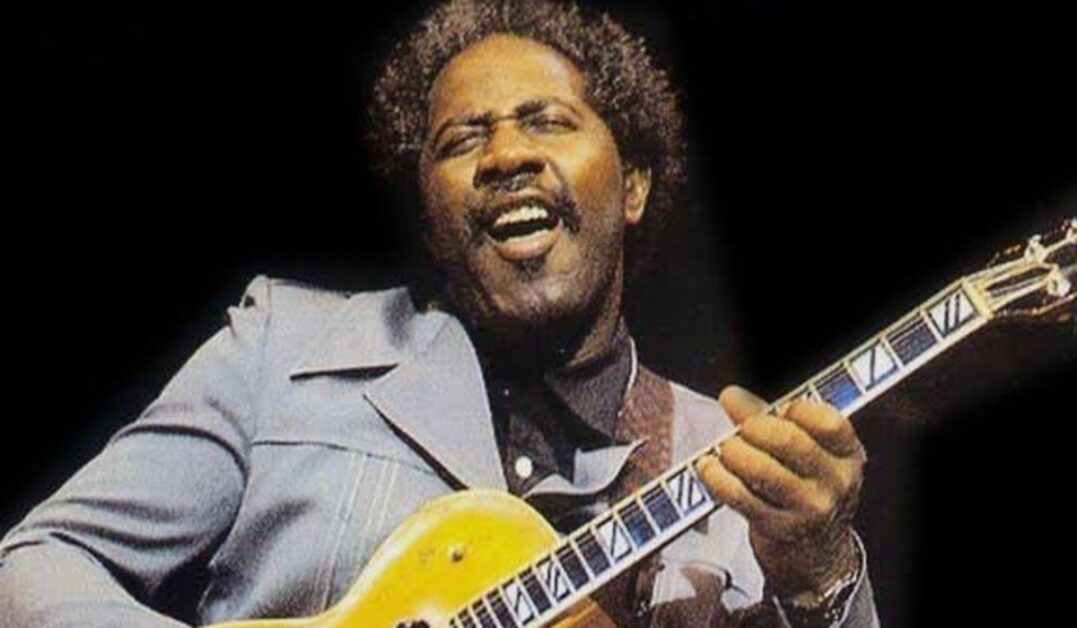

Lost in the confusion was Palmer’s last offering, 2003’s Drive, that was given short shrift because of the preceding demonstration of a seeming lack of direction, and the fact that it’s a fairly straight ahead Blues record. Unfortunately, Blues is a hard sell; and, in this instance, more so when coupled with the credibility factor of the suave Robert Palmer doing a Blues album.

It’s rather unfortunate because Drive is a really good record.

The stylized insert photo portrays Palmer holding a cigarette, and the gutbucket vocals on the disc give the distinct impression that he smoked a carton of them before going into the studio. Like nothing Palmer has ever done before, the production values are akin to a vintage Blues recording with standard Blues instrumentation complete with harp. The result is a rendering of 10 credible Blues / R&B covers. (There are 12 cuts but Palmer couldn’t help himself; he had to include other genres: Adult Contemporary – “Dr. Zhivago’s Train” – and World Beat – “Stella”). The album opens with a rocking rendition of J.B. Lenoir’s “Mama Talk To Your Daughter”; and other highlights include Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog”, Bobby Bland’s “Who’s Fooling Who”, and Little Willie John’s “I Need Your Love So Bad”.

Throughout Robert Palmer’s career, he remained a very private person.

The thrice married Palmer obviously had a love for women as evidenced by his album covers and videos, but there were no salacious rumours or sordid tales that made the tabloids. The Rock star life held little appeal, and there were no stories of an ill-behaved Palmer heaving TV’s out hotel windows. As he said in interviews, he avoided unwanted scrutiny by always working on the next musical project; (Palmer proved to be proficient on a number of instruments over the years and he prided himself in having built a state of the art home recording studio).

One aspect of the star making machinery that Palmer always paid close attention to was promotion.

He welcomed going on promotional junkets (“it’s part of the job”), and was always gracious and accommodating in all of his dealings with the press. It’s stuff of legend that, in the 80’s, Palmer would show up for a round of interviews with a pack of Dunhills and a bottle of single malt that he would steadily work his way through in the course of the exchanges.

Palmer moved to Lugano Switzerland in the 90’s and lived there till his untimely death.

He and his partner Mary Ambrose were vacationing in Paris when Palmer died suddenly after suffering a massive heart attack on September 26, 2003. He was 54.

Despite his time in the spotlight Robert Palmer was never really appreciated. With everything he brought to the table, Robert Palmer was truly a cut above.

A SELECTED ROBERT PALMER PLAYLIST

- Rico Ferrara, October 2021

Leave a Comment