Bobby “BLUE” Bland – Blue is His Middle Name For a Reason

Posted on by Rico Ferrara – Blues For A Big Town Blog

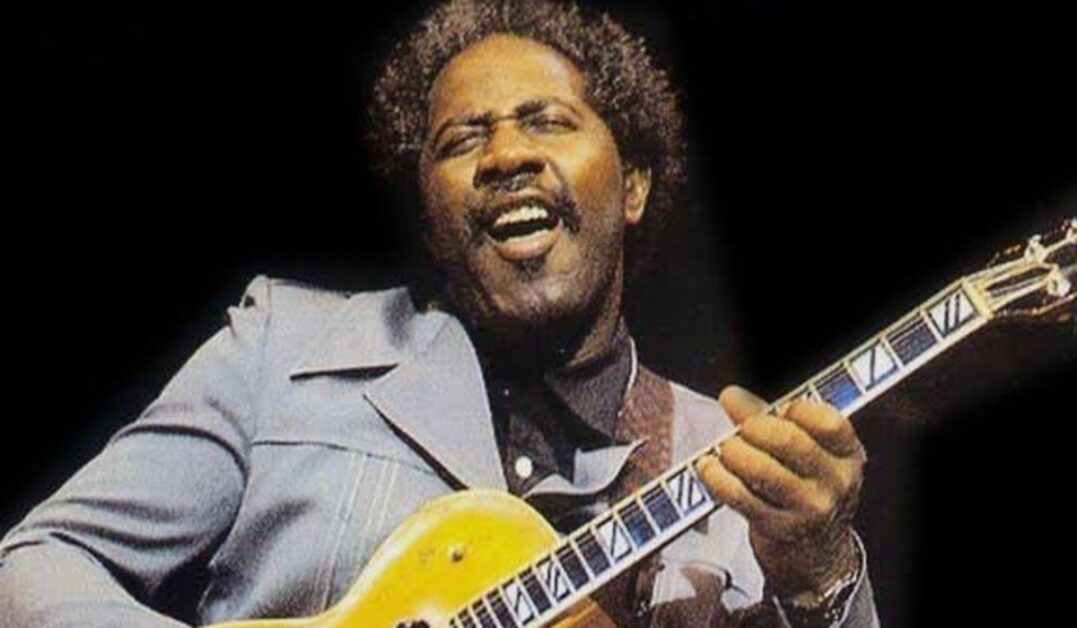

“He’s my favourite Blues singer.”

BB King

“Bobby Bland was just the man…He had exceptional delivery and understanding. He made you understand what the song means to him”

Dan Penn, celebrated Southern Soul songwriter and singer

“He is considered the pioneer of a distinct form of R&B called ‘Soul Blues’ thereby influencing a host of later Blues singers. Bobby Bland brought the sound of Black Gospel music into the Blues and thereby helped transform Black music of the 1950’s into the Soul style of the 60’s”.

Robert Palmer, N.Y. Times

My first memory of Bobby “Blue” Bland was seeing him on TV on The Lloyd Thaxton Show around 1965.

The L.A. based Thaxton show, in full swing in the 60’s, was fashioned somewhat similarly to the more popular American Bandstand. That is, among other elements, it was primarily a teenage dance party with featured musical guests. Where it differed was the selection of those musical guests that coincided with the eclectic tastes of the Memphis born Thaxton. Audiences would just as likely see Sonny & Cher and The Byrds as they were to see Les McCann, James Brown, Solomon Burke, and Bobby Bland.

On this particular day, not being familiar with Bland, I can’t remember the song that he performed. What I do recall was that it was more polished, sophisticated, and “adult” than what I was used to listening to. I filed it away with the thought that Bland didn’t have enough grit to suit my tastes.

It’s three years later and I’m listening to my “go-to” station for Soul – WUFO out of Amherst NY.

After a brief intro, the airwaves were filled with Bland singing “Save Your Love For Me”, a marked departure from the Wilson Picketts, Otis Reddings, and Sam & Daves of this world, that were in constant rotation on the station. While acknowledging my initial impression of three years previous, this time I was drawn in. It was the swell of the introductory horns, that voice, (that B.B. King would refer to as “satin”), and the attention to detail in the shaping of the lyrics.

The voice and the diction brought those lyrics to life and haunted me for days after:

I wish I knew / Why I’m so in love with you / There’s no one else in this world will do / Darling, please save your love for me. The song may have originated with Nancy Wilson, and also been credibly covered by a number of artists, but Bland’s take will always stay with me as the definitive version. Having already decided that Sam Cooke was the best singer on the planet, now I was thinking Bobby Bland should be held in high regard as well and why ‘Blue is His Middle Name For a Reason’

Little did I know of the hard work that was put forth in perfecting those vocals and the overall approach that would result in the much copied but never duplicated the Bobby Bland sound

or of that diligence resulting in Bland having the fourth highest number of singles placed in the R&B charts in the course of the 60’s. (Included in those hits were three that garnered #1 status: “I Pity The Fool” 1961, “That’s The Way Love Is” b/w “Call On Me” 1963, and Bland’s highest crossover hit “Ain’t Nothing You Can Do” 1964).In defence of my unawareness of Bland’s stature, his releases weren’t on a comparatively more visible and well distributed Black oriented label such as Motown or Stax.

That this fact didn’t detract from Bland’s obvious success is due to Bland’s camp’s selectivity to capitalize on Bland’s appeal with a mature, female dominated, African American market rather than target one of more mass prospects. (While stating this well laid out strategy, it’s noted that Stax also mined the African American market but was not one who’s energies were directed specifically to a female weighted audience).

The direction taken wasn’t simply a marketing ploy, but one that coincided with Bland’s personal preference as well as one that took advantage of his rich baritone, urbane style, and sensual delivery.

In opposition to the “hard Blues” of the day that Bland explained “… I never did care for really”, Bland offered quiet pleading, a sense of humility, and a soothing vulnerability (with obvious appeal for the ladies). Further, Bland explained the mindset and point of difference this way:

“I kept wondering what would happen if I took the growl out of the Blues and replaced it with some kind of mellow moan. Would people still like it or call me a traitor to the Blues? It didn’t take long to learn that the women sure enough liked it and brother that’s all I needed to know”.

Bobby Bland

The man, who would go on to be known at various times as “the Black Frank Sinatra”, got his love for music – and singing in particular – at a young age, growing up in his birth home of Rosemark Tennessee, (population 500, located 25 miles north east of Memphis).

After a local musician and Blues singer, Mutt Piggee, spurred his musical interest, young Bobby could be found on the street corners of Rosemark singing “Hillbilly Music”, (that he learned listening to The Grand Ole Opry), for nickels and dimes. It was a pastime that Bobby much preferred to picking cotton and attending school. In fact, Bobby would only get as far as grade three and would go through life without ever learning to read or write.

Bobby and his mother learned to rely on each other and formed a close bond after his biological father abandoned the family.

His mother would re-marry and Bobby would take his step father’s surname, “Bland’. It was with Bobby’s future prospects in mind that his mother initiated the move to Memphis when Bland was 17 years old. Her reasoning was that the move would give Bobby a chance to follow through on his interest in singing, all the while fearing that – with his aversion to school – he would end up picking cotton if they stayed in Rosemark. Alternatively, Memphis, at that time viewed as the focal point of the Mississippi Delta, and referred to by southerners as “The main street of Negro America”, offered the possibility of some level of prosperity.

In Memphis Bobby worked at various jobs including washing dishes and cleaning up at his mother’s restaurant, delivering groceries on a second hand bike, and working at a local garage.

But it was learning to drive and getting his driver’s license that provided freedom, opportunity, and that would pay dividends both immediately as well as down the road. Instantly, it offered a new revenue stream generated by parking cars at The Peabody Hotel as well as driving labourers from Downtown Memphis to cotton fields in Mississippi and Arkansas, and driving prospective customers to local bootleggers.

Singing remained Bland’s main interest,

He attended the Baptist Church with his mother and sang in the choir. In addition, on weekends, he sang Spirituals with The Miniatures – a group of five that patterned themselves after The Pilgrim Travelers. The Travelers were a Houston based collective that was popular in the 40’s and 50’s and whose members included among others, Lou Rawls. And while Bland listened intently to other popular Gospel groups of the day, i.e. The HWY QC’s, The Mighty Clouds Of Joy, The Soul Stirrers, and his personal favourites Ira Tucker & The Dixie Hummingbirds, he also started frequenting Beale Street.

Bland felt a certain kinship with the more refined, Jazz oriented artists on Beale rather than the gritty Blues predominantly found in the bars or Handy Park, (where many aspiring Blues musicians ventured to showcase their talents including B.B. King).

His artists of choice matched those that Bobby listened to and would prove to be a major influence: Amos Wilburn, Charles Brown, Lowell Fulson, T-Bone Walker, Louis Jordan. Jimmy Witherspoon, and Nat King Cole. It was also on Beale that Bland started hanging around “with a bunch of guys” in the early 50’s who became known as The Beale Streeters.

The Beale Streeters were a loose affiliation of performers that often backed one another, and included at one time or another B.B. King, singer / piano players Johnny Ace and Roscoe Gordon, drummer Earl Forrest, and sax man Adolph Duncan.

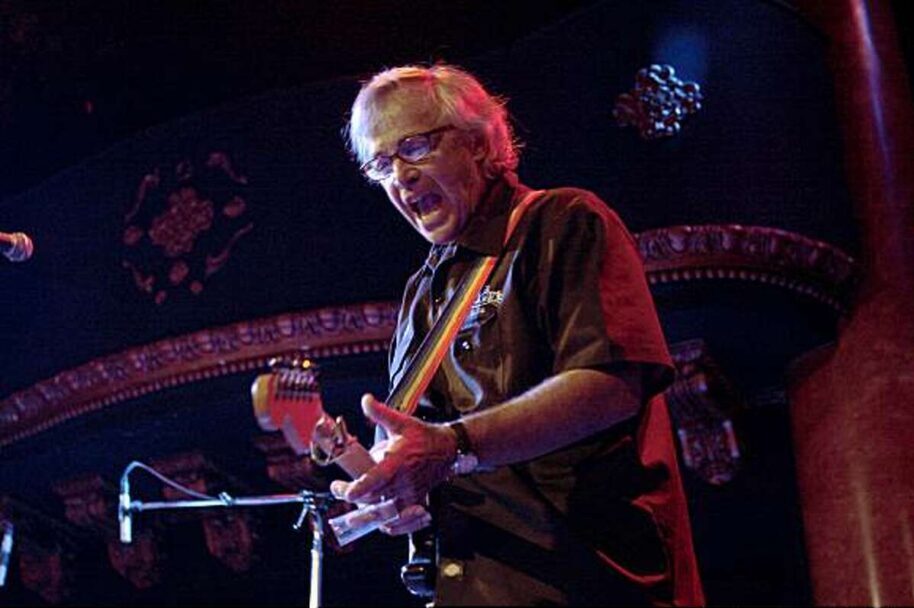

It was through this association that Bland started a lifelong friendship with B.B. King who was 5 years his senior. Bobby said of B.B.: “I idolized him and still do”.B.B., refuted the much repeated claim that Bland was his valet.

Instead, King would welcome Bland’s open offer to help in any way, including driving duties. Bland did so in the hopes of learning as much as he could from his hero both in performance and about the business. Ever thankful, Bland said of B.B.: “He let me hang around and get some kind of experience”.

Bland admitted that he was initially on the fringe of The Beale Streeters; that while he continued to sing, he was rough, had bad timing, and had no style of his own.

(At this point in time he was relying primarily on a falsetto that he copied from B.B. King). But he forged on including participating at Amateur Night at The Palace Theatre. MC’d by then WDIA disc jockey Rufus Thomas, similar to Apollo Amateur Night, The Palace presented a tough environment for contestants. In addition to musicians, there were magicians, acrobats, jugglers, comedians, and others with assorted talents that were subjected to an audience that hurled tomatoes and various sundry items. And, if that wasn’t enough, the competition featured the “Lord High Executioner” who would leap from the wings and shoot a blank gun at many an uninspiring contestant. Contestants were judged by applause, and winners would be awarded $1 for their efforts. Like other contestants, Bobby Bland entered not for the $1 prize but the hope of catching a talent scout‘s eye. Bland won on a number of occasions thus opening the door to his first recording dates.

Nothing commercially significant resulted from these sessions that were recorded in 1950 and 1951 on various independent labels including Chess, Modern, and Duke.

Usually “scheduled” when there was remaining studio time at the tail end of someone else’s session, the recordings went nowhere and were quickly forgotten. However, there was some interest generated in that David J. Mattis, the owner of Duke Records, signed Bobby to his first recording contract in 1951 when Bobby was 21 years old.

Bobby’s hopeful road to stardom hit a snag when he was drafted into the army.

While “running in place” as he waited to resume his quest for a music career, he still managed to find opportunities to sing. By the end of his tour Bobby was performing in Special Services, the entertainment branch of the American military. Special Services – one of the few U.S. Army units to be racially integrated at the time – was created to provide recreational opportunities for the servicemen, with the objective of boosting morale.

For his part, Bobby covered material by Nat King Cole and Charles Brown. Always looking to learn, improve, and remain current with trends, Bland continued to listen to whatever was hot on the jukebox. In so doing, he started to gravitate to the “softness” of such singers as Tony Bennett, Billy Eckstein, and Perry Como – a trait that Bland would later incorporate as he found his own style.

After being discharged in 1955 Bland started working with the already established Junior Parker who, at the time, was leading his own band The Blue Flames.

Bobby assumed a defined support role with Parker in that he did the driving, set up the bandstand, and opened the show. Presenting themselves as “Blues Consolidated”, starting in 1956 they hit the road playing stops on the Chitlin’ Circuit – venues found generally in southern areas of the U.S. that were played almost exclusively by Blacks for Black audiences. Bland stayed with Parker till 1961 before he went out on his own (and initially taking The Blue Flames with him).

Like Bland, Parker was a Duke recording artist and had to adjust to the intimidating business practices of the new sole owner of the label, club owner and entrepreneur Donald Deadric Robey. Robey, who would play a vital role in Bland’s career, had formed a partnership with then owner David Mattis in 1952.

Wanting to run the business on his own terms, Robey sought to gain full control of the label; and was successful in doing so in 1953. (In illustration of Robey’s way of dealing with obstacles in his path is an often told story of his meeting with Mattis with the sole purpose of negotiating a buy-out. At the outset of the meeting Robey supposedly put a pistol on the table to demonstrate, in no uncertain terms, his determination to get his way).As the new owner of the Duke label, Robey drew up new contracts for the various Duke artists including Bobby Bland.

Knowing that Bland couldn’t read or write Robey helped him sign a contract that awarded Bland ½ ₵ per recording instead of the industry standard of 2₵.

In variation of this theme, Robey also bought or stole songs assuming songwriting credits as well as accompanying royalties under the pseudonym of “Deadric Malone”.

When questioned on such Robey strong arm tactics, Bland defended Robey and his time at Duke mentioning a family environment and saying:

“Well he’s in business. Each company that you get with does the same thing. But Robey did a lot of people a lot of favours, like me for one. Getting a chance to record”.

Bobby Bland

While honourable in his loyalty to Duke and Robey, it should be taken into consideration that the shy, insecure Bland – who at times had to be led – needed, more so than other artists, what he perceived as Robey’s paternalistic posture.

If nothing else, it’s to Robey’s credit – regardless of how the songs were obtained – that he knew good material, and had a sense as to what songs fit Bland the best. And it goes without saying that the tracks that Bland recorded in the 20 years that he was on the label represented the apex of his career.

Not only were there numerous hits on the R&B charts – many of which having become Blues / R&B standards – but more than 2/3 of those hits crossed over into the Pop charts.

His first major hit, 1957’s “Farther On Up The Road”, was followed by a long line of memorable songs including: “It’s My Life Baby”, “I Smell Trouble”, “Little Boy Blue”, “Cry Cry Cry”, “Don’t Cry No More”, “Ain’t That Lovin’ You”, “Stormy Monday”, and “Turn On Your Lovelight”, among countless others.

Coupled with the single releases were critically acclaimed albums, that contained the aforementioned songs, such as Two Steps From The Blues 1961, (cited by many as one of the best Blues albums of all-time); Here’s The Man 1962; Call On Me 1963; The Soul Of The Man 1966; and Touch Of The Blues 1967. If you’re not familiar with the titles, suffice to say that they’re all well worth searching out. Lastly, it can truthfully be said, in addition to those mentioned, there’s merit to be found in all of Bland’s Duke albums.

It was around 1957, that Bland’s singing style started to emerge.

Among the honing of vocals skills that was to follow, having lost the falsetto that he had adapted, he felt the need to develop “another gimmick”. That device was his signature squall that he admitted was lifted from Gospel records by Rev. C. L. Franklin (Aretha’s father). Specifically, he got it from Franklin’s “The Eagle Stirreth His Nest”.

But the squall is only one element in the evolution of the Bobby Bland voice and overall sound.

Playing a crucial role in that development was arranger, band leader, and occasional 1st trumpeter Joe Scott. No one was more influential in Bobby’s career than Scott; to the point that in some circles it was said that Bobby Bland was Joe Scott’s creation. Bland’s perspective didn’t veer very far from that viewpoint: “I would say he was everything. Without Scott I wouldn’t be the singer I am”.

Joe Scott was fully in charge of Bobby Bland’s band and method from 1958 through 1968 thereby overseeing Bobby Bland’s most revered work including the recording of Two Steps From The Blues.

He arranged the sessions, hired the musicians, and demonstrated an instantly clear vision of the sound he wanted. He built on the existing Bobby Bland sound – that centred on spare Blues accompaniment featuring traditional Blues guitar – by adding a new dimension of bold brassy horn arrangements that became an integral part of the Bobby Bland sound. Those arrangements borrowed from the Big Band sound of the 40’s – with the likes of Louis Jordan, Lional Hampton, and Count Basie in mind – and bridged them with the Soul revues of the 60’s. Lastly, the arrangements had a free swinging quality that made them quite unique

At the same time, recognizing Bobby’s existing vocal talents and growth potential, Scott spent countless hours with Bobby perfecting his diction and phrasing in addition to teaching him the proper approach to a lyric, and mic technique.

Taking Scott’s lead, it’s been said that Bobby would work on a song for endless hours, breaking down its components while looking to master to every aspect of a song. Only after such successful attention to detail was a song deemed ready for live performance and / or recording.

The final element, with the objective of maintaining a link to the Blues tradition while remaining contemporary and providing an earthy quality, Scott continued with the employment of a scorching guitar player such as Pat Hare, or Clarence Hollimon, or possibly the most famous, Wayne Bennett. (Those are Bennett’s superb lines on Bland’s take on T-Bone Walker’s “Stormy Monday”).

Although continuing to work together periodically, Scott and Bobby, for all intents and purposes, parted ways in 1969. But the groundwork had been laid, and Bland learned his lessons well. Learnings that would hold him in good stead for the rest of his career.

Bobby Bland earned his popularity, and a corresponding reputation, not only from his critically acclaimed and commercially successful recordings but also from constant touring that helped get the word out about his talent and artistry.

In his prime Bland played more than 300 one nighters annually. And, solidifying his following with, and maintaining his ties to the African American audience, he continued to perform in juke joints, country fairs and cafes, and Black Blues dinner clubs in the South among his many appearances.

Duke was sold to MCA in 1973. Although the Duke years set a high bar; and Bland was, in effect, competing with himself, the book wasn’t closed on Bobby Bland as some critics might have you believe. Maybe not quite as dominant, but there were more noteworthy chapters in that book as Bland’s career continued, including his time at MCA, for another 30 years.

Shade was cast on the MCA years by various critics because of geographical factors and what was perceived as a more commercial direction taken in the music.

Geographical in that the work was recorded in L.A.; and viewed as somewhat foreign turf, and not fitting the Bobby Bland persona. As far as the music was concerned, listeners were cautioned that the studio band was comprised of slick session players who had no real affinity for the material – material deemed not worthy of an artist of Bland’s background and stature. Further, the recordings were presided over by Steve Barri and Michael O’Martian, who had a background in Pop rather than one in Blues or R&B.

Given all of that, his albums sold respectably, as Bland maintained a strong following. In particular the first two releases: His California Album and Dreamer merit a mention. “California” contained the R&B Top Ten “This Time I’m Gone For Good”; and Dreamer featured his follow-up single “I Wouldn’t Treat A Dog” that finished in the Top Five R&B. It also must be said that MCA and its’ distribution helped Bobby expand his listenership beyond his established Black audience. (Capitalizing on his “new found fame”, Bobby reunited with B.B. King on record with two highly regarded albums: a studio effort Together For The First Time and a live recording of their performance at The Coconut Grove in L.A., Together For The First Time… Live.)

Bobby’s next, (and last), stop was Malaco Records in Jackson Mississippi where he signed on in 1985 and would stay for 18 years.

Differing from Bland’s MCA experience, Malaco directed concerted efforts to a Black audience. Accordingly, the record company brought Bobby closer to a core African American audience that he had spent his entire career courting. Malaco also provided Bland with artistic freedom and encouragement that moved Bobby to remark: “Malaco had a family atmosphere like Duke used to have”.

Bland responded to Malaco’s confidence in him by recording a dozen albums and receiving 7 Grammy nominations for those releases. Meriting special mention is Midnight Run that Bobby released in 1990 and stayed on the R&B charts for over a year and a half.

Bobby Bland justifiably received recognition for outstanding achievement over the course of his career including the following:

- Inducted into the Blues Hall Of Fame in 1981

- Inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame in 1992

- Received the R&B Foundation Pioneer Award in 1992

- Received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997

- Inducted into the Grammy Hall Of Fame in 1999

Robert Calvin Bland died of congestive heart failure on June 23, 2013. He was 83 years old. Forever a humble man, Bobby stated in an interview:

“I’d like to be remembered as just a good old country boy that did his best to give us something to listen to and help them through a lot of sad moments, happy moments, whatever”

Bobby Bland

Bobby “Blue” Bland did just that.

Rico Ferrara June 2022